Complications with biological data

Last updated on 2026-02-24 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- When are Fisher- and Chisquare test not applicable for biological data?

- What are alternative methods?

Objectives

- Explain overdispersion and how it can lead to false positives.

- Explain random effects.

- Name some alternative methods.

Overview

The lesson has been using a very simple example to illustrate the principles behind analyzing categorical data.

Of course, biological data are often more complex than can be captured by a \(2\times2\) table.

Some examples for this are:

- There are more than two categories per variable. For instance, 3 different treatments are applied on cultured cells, and individual cells are subsequently categorized into 4 mutually exclusive phenotypes.

- There are more than two variables. For instance, the above experiments could have been carried out in three replicates, such that replicate is the third variable. We are looking for an effect that is consistent across replicates.

Larger tables

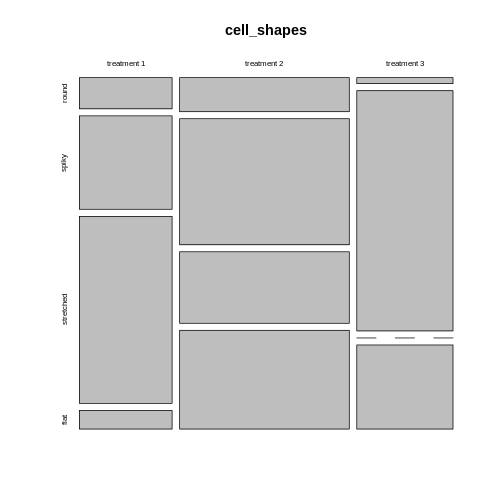

Let’s start with the first example, where 3 different treatments are applied on cultured cells, and individual cells are subsequently categorized into 4 mutually exclusive phenotypes. The resulting contingency table could look like this:

| round | spiky | stretched | flat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment 1 | 5 | 15 | 30 | 3 |

| treatment 2 | 10 | 37 | 21 | 29 |

| treatment 3 | 1 | 40 | 0 | 14 |

How to visualize the proportions?

We can still use mosaic plots to visualize the proportions:

R

cell_shapes <- rbind(c(5,15,30,3), c(10,37,21,29), c(1,40,0,14))

rownames(cell_shapes) <- c("treatment 1","treatment 2", "treatment 3")

colnames(cell_shapes) <- c("round", "spiky", "stretched", "flat")

mosaicplot(cell_shapes)

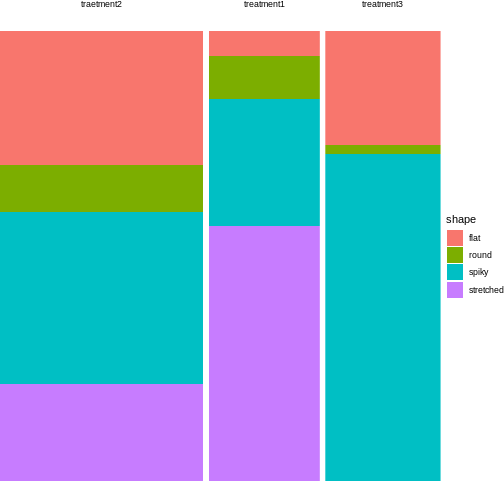

For the brave

Can you turn the cell_shapes table into tidy data, and

make a mosaic plot with ggplot2?

The tricky part is data wrangling:

R

tidy_shapes <- data.frame(cell_shapes, treatment=c("treatment1", "traetment2","treatment3")) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = 1:4,

names_to = "shape",

values_to = "count")

tidy_shapes

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 12 × 3

treatment shape count

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 treatment1 round 5

2 treatment1 spiky 15

3 treatment1 stretched 30

4 treatment1 flat 3

5 traetment2 round 10

6 traetment2 spiky 37

7 traetment2 stretched 21

8 traetment2 flat 29

9 treatment3 round 1

10 treatment3 spiky 40

11 treatment3 stretched 0

12 treatment3 flat 14For plotting, all you need to do is exchange the variable names from the instructions in episode 3:

R

tidy_shapes %>%

group_by(treatment) %>%

mutate(sumcount = sum(count)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=treatment, y = count, fill=shape, width=sumcount)) +

geom_bar(stat="identity", position = "fill") +

facet_grid(~treatment, scales = "free_x", space = "free_x")+

theme_void()

Looks much nicer, doesn’t it?

Looks much nicer, doesn’t it?

What are suitable measures for association?

All the measures you learned about are require a \(2\times2\) table. The good news is that you can subset or summarize your \(4\times3\) table into smaller tables and calculate odds ratios or differences in proportions on them.

For example, you could compare treatment 2 and 3 with regards to the ratio of flat and round cells. For this, you subset the table to the relevant rows and columns:

R

shapes_subset <- cell_shapes[2:3,c(1,4)]

shapes_subset

OUTPUT

round flat

treatment 2 10 29

treatment 3 1 14The odds for being round (vs. flat) in treatment 2 compared to treatment 3 are:

R

(10/29)/(1/14)

OUTPUT

[1] 4.827586If you are rather interested in the overall proportion of round cells, still comparing treatment 2 and 3, you can subset the columns and summarize some of the rows:

R

round <- cell_shapes[2:3,1,drop=FALSE]

others <- cell_shapes[2:3,2:4,drop=FALSE] %>% rowSums

shapes_summary <- cbind(round,others)

shapes_summary

OUTPUT

round others

treatment 2 10 87

treatment 3 1 54Now you can compare the proportions of round cells between the treatments 2 and 3:

R

(10/(10+87)) / (1/(1+54))

OUTPUT

[1] 5.670103The proportion of round cells is 5 times higher in the experiment with treatment 2.

You probably noticed that with larger tables, you have many more options of sub-setting or summarizing them into \(2\times2\) tables. Think carefully about your research question and then decide which comparison you’d like to make.

How to calculate significance?

As soon as you have subset or summarized your larger table into a \(2\times2\) one, you can apply the standard Fisher or \(\chi^2\) test on it, and we’ll come back to this very soon.

But luckily, Fisher’s exact test and the \(\chi^2\) test can also be applied to 2D tables with more than two categories in each dimension, and this should actually be the first step in your hypothesis testing workflow.

A Fisher test on the above \(3\times 4\) table will answer the following question: Is there a difference in phenotype composition between the three treatments?

This is an overall question and it’s controlling for the family-wise error rate. If this test comes out significant, it tells you that under the assumption that phenotype and treatment are not associated in any way (i.e. for each phenotype, the underlying proportion doesn’t vary between treatments), your results are very unlikely.

For the above example, the \(\chi^2\) test is clearly significant:

R

chisq.test(cell_shapes)

WARNING

Warning in chisq.test(cell_shapes): Chi-squared approximation may be incorrectOUTPUT

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: cell_shapes

X-squared = 62.024, df = 6, p-value = 1.744e-11Now you could do follow-up tests in order to find out which phenotypes are different in their proportions between treatments, for example:

R

fisher.test(shapes_summary)

OUTPUT

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

data: shapes_summary

p-value = 0.05797

alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is not equal to 1

95 percent confidence interval:

0.8335549 273.9339822

sample estimates:

odds ratio

6.154128 Just as for calculating measures of association, you should ask yourself what information you’re after, before running 10 or more individual comparisons.

3D tables

Note: The notation for this section is borrowed from these materials.

For higher-dimensional tables, life gets yet a bit more complicated. Again, there are different ways of analyzing them, dependent on your research question.

Let’s consider a similar experiment to the one above, where a control and a treatment are compared with respect to the phenotype composition of cells. In this experiment, there are only two possible phenotypes: round and stretched.

A resulting table might look like this:

| round | stretched | |

|---|---|---|

| ctrl | 9 | 39 |

| trt | 21 | 42 |

This still looks familiar. But now, the biologist at work was concerned about the reproducibiliy of the experiment, so she performed it three times. And as a result, we look at a 3-dimensional table, with the replicate as third dimension:

|

|

|

How to create a 3-D table in R

In this lesson, you have seen two versions of representing count data:

- As an array

- As a data frame in tidy format

Coding up the data

R

table1 <- rbind(c(9, 39), c(21,42))

table2 <- rbind(c(16, 59), c(51,99))

table3 <- rbind(c(7, 40), c(22,41))

table3d <- array(c(table1, table2, table3), dim = c(2,2,3))

table3d

OUTPUT

, , 1

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 9 39

[2,] 21 42

, , 2

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 16 59

[2,] 51 99

, , 3

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 7 40

[2,] 22 41A data frame in tidy format would look like this:

R

rep1 <- data.frame(

replicate = rep("1",4),

trt = c(rep("ctrl",2), rep("trt",2)),

shape = c("round","stretched", "round", "stretched"),

count = c(9, 39, 21 ,42)

)

rep2 <- data.frame(

replicate = rep("2",4),

trt = c(rep("ctrl",2), rep("trt",2)),

shape = c("round","stretched", "round", "stretched"),

count = c(16, 59, 51, 99)

)

rep3 <- data.frame(

replicate = rep("3",4),

trt = c(rep("ctrl",2), rep("trt",2)),

shape = c("round","stretched", "round", "stretched"),

count = c(7, 40, 22, 41)

)

tidy_table <- rbind(rep1, rep2, rep3)

tidy_table

OUTPUT

replicate trt shape count

1 1 ctrl round 9

2 1 ctrl stretched 39

3 1 trt round 21

4 1 trt stretched 42

5 2 ctrl round 16

6 2 ctrl stretched 59

7 2 trt round 51

8 2 trt stretched 99

9 3 ctrl round 7

10 3 ctrl stretched 40

11 3 trt round 22

12 3 trt stretched 41We’ll come back to the tidy format later in this lesson. For this episode, we stay with the 3D table in array format.

Conditional independence

In data with replicates, we usually expect that the replicates behave

similarly and that evidence from the replicates can be aggregated. In

our example, we expect similar odds ratios in all three replicates. We

can confirm this by extracting the odds ratio estimates in the

fisher.test function for each of them:

R

fisher.test(table1)$estimate

OUTPUT

odds ratio

0.4647027 R

fisher.test(table2)$estimate

OUTPUT

odds ratio

0.5278675 R

fisher.test(table3)$estimate

OUTPUT

odds ratio

0.3293697 We can also look at the p-value for each \(\chi^2\)-test:

R

chisq.test(table1)$p.value

OUTPUT

[1] 0.1340615R

chisq.test(table2)$p.value

OUTPUT

[1] 0.0712236R

chisq.test(table3)$p.value

OUTPUT

[1] 0.03239296The p-value of the \(\chi^2\)-test is only \(<0.05\) for the third replicate, meaning that for replicates 1 and 2 there is not enough evidence for an association between treatment and morphology. But if we take the three replicates together, what will the overall conclusion look like?

Discussion

We could easily bring the above scenario down to a classical \(2\times2\) table by pooling the counts across replicates. What could be problematic about this approach?

The replicate might have an effect on the row and column sums. Have a look at the Simpson’s paradox.

Let’s try it

Use the above code for creating an array and sum up the counts across replicates.

R

rowSums(table3d, dims=2)

OUTPUT

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 32 138

[2,] 94 182To avoid the danger of replicates being confounded with a variable of interest, one should stratify by replicate. Stratify means: split the analysis by replicate, and then combine the results.

This is what the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test does. It calculates

- a common odds ratio and

- a modified chi-square,

taking the replicates into account.

Let’s stay with the examples above:

| 9 | 39 |

| 21 | 42 |

| 16 | 59 |

| 51 | 99 |

| 7 | 40 |

| 22 | 41 |

We’d like to test whether the composition of cell types is independent of the treatment, and at the same time stratify by replicate (i.e. look at the replicates separately).

We say that we test for conditional independence, because we are interested in the independence of cell type composition and treatment, and we test conditional on the replicate.

The null hypothesis is:

\(H_0: \Theta_{XY(1)} = \Theta_{XY(1)} = ... = \Theta_{XY(K)}=1\)

with \(\Theta_{XY(i)}\) being the odds ratio between the variables X and Y for repliate \(k\).

How can we do this? For each replicate, we have a \(2\times 2\) table, on which we could run a \(\chi^2\)-test, based on the \(\chi^2\) statistic. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test is based on a very similar statistic:

\[ M^2 = \frac{\lbrack\sum_k(n_{11k}-\mu_{11k})\rbrack^2}{\sum_k Var(n_{11k})} \] with

\[\mu_{11k} = E(n_{11}) = \frac{n_{1+k} n_{+1k}}{n_{++k}}\] and

\[\text{Var}(n_{11k}) = \frac{n_{1+k}n_{2+k} n_{+1k} n_{+2k}}{n^2_{++k}(n_{++k}-1)}\]

Under the null hypothesis, \(M^2\) follows a chi-square distribution with 1 degree of freedom.

We don’t need to go into the details of how variance is calculated, but notice that in the numerator, the counts for each replicate \(n_{11k}\) are compared to an expected value \(\mu_{11k}\) (expected under the null), which is calculated from that same replicate \(k\). The squared differences between expected and observed from each replicate are then summed up to constitute the across-replicates statistic \(M^2\). That way, each replicate is first treated separately, and then results are combined.

The p-value from the Cochran-Mantel-Haneszel test tells us whether we have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis that the odds ratios for all replicates are 1.

In R, we can run this test on a 3D table like the one created above:

R

mantelhaen.test(table3d)

OUTPUT

Mantel-Haenszel chi-squared test with continuity correction

data: table3d

Mantel-Haenszel X-squared = 10.895, df = 1, p-value = 0.000964

alternative hypothesis: true common odds ratio is not equal to 1

95 percent confidence interval:

0.2869095 0.7185351

sample estimates:

common odds ratio

0.4540424 The test is highly significant. By aggregating the information from all three replicates, we were able to increase the power of the test.

The test also gives a common odds ratio, which is estimated as \(\widehat{OR}_{MH} = 0.780\).

It is calculated as follows:

\[\widehat{OR}_{MH} = \frac{\sum_k(n_{11k}n_{22k})/n_{++k}}{\sum_k(n_{12k}n_{21k})/n_{++k}}\]

Remember that the odds ratio for a \(2\times2\) table is calculated as

\[\widehat{OR}=\frac{n_{11}n_{22}}{n_{12}n_{21}}.\] So the common odds ratio is similar to a weighted sum of individual odds ratios, where those partial tables (=replicates) with more total counts have more impact on the OR estimate.

Homogeneous association

The common odds ratio and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test assume homogeneous association: the conditional odds ratios (i.e. odds ratios for each replicate) don’t depend on the replicate. The marginal distributions of the two variables might still change between replicates, this is not contradicting homogeneous association.

For example:

- If the fraction of treated cells is different in replicate 1 than in replicate 2, this is alone doesn’t exclude homogeneous association. The odds ratios could still be the same in both replicates.

- If in replicate 1 the fraction of untreated round cells is twice the fraction of treated round cell, while in replicate 2 the fraction of untreated round cells is half the fraction of treated round cells, then homogeneous association is (likely) not met.

Ways to check for homogeneous association include:

- calculating individual odds ratios for the partial tables

- eye-balling the data, e.g. through the mosaic plots

- formal testing using the Breslow-Day-test

- formal testing for a three-way interaction (see below).

Three-way interactions

There are situations where you may be interested in how a third variable influences the association between the other two. Let’s assume in the example above, you don’t have two replicates, but instead measured the association between treatment and cell shape in two different temperatures. Your hypothesis is that the effect of the treatment on cell shape composition is temperature-dependent. This question does not come with an off-the-shelf test to address it.

Instead, we have to switch to a method called generalized linear model. Actually, it’s not so much of a switch, but a change in perspective, as both Fisher test and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test can be seen as special cases of generalized linear models. In a generalized linear model, an association between two variables - such as cell shape and treatment, which we investigated using the Fisher test - is called a two-way interaction, and the association between three variables - such as cell shape, treatment and temperature - is called a three-way interaction. In the next episode, we’ll explain generalized linear models in more detail.

Additional variance

When we’re using Fisher’s or \(\chi^2\) test, we model the data as having been obtained from a particular sampling scheme, like Poisson, binomial or multinomial sampling. These assume that there is an underlying rate, or probability, at which events occur, and which doesn’t vary. For example, we could say that patients show up at a hospital at an average rate of 16 patients per day (\(\lambda=16\)), and if we took 5 samples at 5 different days, we’d assume the same Poisson rate for each day. The counts would vary from day to day, but with a variance of \(var=\lambda\), which is the expected randomness for a Poisson counting process. See also the lesson on distributions.

The problem is, that in biology, we often have experiments where we deal with additional variance that can’t be explained by the normal variance that’s inherent to Poisson counting. For example, if we model read counts from RNA sequencing, it turns out that the (residual) variance is much higher than \(\lambda\), because the expression of a particular gene usually depends on more factors than just the experimentally controlled condition(s). It is also influenced by additional biological and possibly technical variance, such that the counts vary considerably between replicates.

Why is this a problem?

If we still analyze these data with methods that assume Poisson variance, this increases the risk for false positives. Intuitively speaking, the increased variance can produce extreme counts in one or more of the cells, leading to higher proportions than would be expected by chance under the assumption of independence and Poisson sampling. So the Fisher test can mistake noise for a difference in proportions.

What to do?

First of all, think about the data that you’re looking at, and how they were produced. If you have several replicates, you have a chance to estimate the variance in your data.

In a typical \(2\times2\) table, you just have one count per cell, and a different condition in each cell, so there is no chance to infer the variance from looking at the data. In this case you have to ask yourself, whether it’s likely that you’re overlooking additional variance, and be aware that the data might not perfectly match the assumptions of your test, so don’t over-interpret the p-value that you get – which is always a good advice.

If you do have several counts per condition, you can consider to model your data using a generalized linear model of the negative binomial family, which we’ll discuss in the next episode.